We're excited and relieved to share that the Alberta government's ad valorem wine tax has been recalled! In its place will be a slight increase on the “flat” tax that wine has traditionally been subjected to in the province, with positive effects on pricing incrementally working their way through retail shelves and restaurant lists over the weeks and months following April 1, 2026.

Dönnhoff Cover Songs

Drinking Compromises

By Al Drinkle

Wine is basically the only alcoholic beverage that I drink. As if this isn't restrictive enough, it probably goes without saying that I'm somewhat particular about the wines that I imbibe. Consequently, I'm adept at sneaking my wine into venues or situations in which bringing your own booze is either highly unorthodox or blatantly illegal. When this is impossible, instead of compromising my preferences and standards I'll usually just drink water—but there are exceptions.

My wife loves Caesars so I'll occasionally drink one with her, especially on alpine getaways. This is a curious compromise of my drinking patterns as it contravenes my dietary proclivities along with my outright dismissal of distillates. When I'm at Rain Dog Bar, I'll ask Bill or one of his talented colleagues to recommend a beer, something that I'll also drink when I find myself mashing slices in Dandy's taproom¹ . At a Japanese restaurant with a thoughtful sake program, I'll likewise accept the counsel of the onsite authority.

The other evening I attended a punk show which, assuming passionate bands, I find to be exhilarating if socially exhausting. As my introversion increases with my years, it's no longer the kind of event that I can attend entirely sober, especially if my social battery has been depleted from a day at the shop. Generally I would pack bottles of Riesling to drain in the alley in between sets, but on this particular evening it was -20C, and despite having enjoyed wine prior to my arrival, the situation dictated that I further augment my social lubrication.

I approached the bar and, in doomed competition with the music, queried the bartender as to what kind of dark beer they had on offer. She responded that Guinness was the only option, and notwithstanding my fanatical opposition to corporate entities, I'm fleetingly sentimental about the brand having visited the St. James Gate Brewery in my early twenties.

The bartender took my money and, to my naive disappointment, handed me a can of Guinness. I caught her attention once more and asked if I could please have a glass. Hesitating for a moment before the vessel materialised, she leaned across the bar to yell in my ear.

“Just don't take the glass into the mosh pit!” she hollered as I fought to contain my laughter.

“I'm 42-years-old,” I replied, “I'm not going anywhere near the mosh pit, with or without this glass!”

She gave me a look that said “whatever” before turning to the next patron and I walked away from the bar, dutifully circumventing the front of the stage where people half my age and twice my intoxication level pummeled the shit out of each other in the name of dancing. It was then that I realised my mistake.

“Wait a minute!” I thought to myself, “I'm not 42… I'm 43!” When I turned to explain my error to the bartender who was busy setting fire to some ornate cocktail, I immediately realised that she would care even less than I did. So I took a nostalgic swig of black froth, carefully inserted my ear plugs, and enjoyed the punk rock mayhem while subconsciously calculating how many hours past my bedtime it was.

¹ It should be mentioned that Rain Dog Bar and Dandy Brewing both have completely respectable, concise wine lists.

An Update on Alberta's Ad Valorem Tax

On April 1st, 2025 the UCP (Alberta government) added an ad valorem tax to the existing flat tax on wine. You can read more about this tax here, but in essence 94.3% of wine in the province has gone up in price, and 64.7% has been affected by the highest tax tier of 15%. Combined with our weak Canadian dollar and record high shipping costs, this additional tax is having disastrous effects on Alberta’s wine & hospitality industry.

Yesterday, Metrovino hosted a press conference attended by a coalition of industry associations to call upon the Government of Alberta to repeal this tax. This coalition consists of the Alberta Hospitality Association, Alberta Liquor Store Association, Wines of British Columbia, Import Vintners & Spirits Association, Wine Growers Canada and Restaurants Canada.

Follow the headlines:

Kabinett Through the Ages and A.J. Adam's Otherworldly 2024s

By Al Drinkle

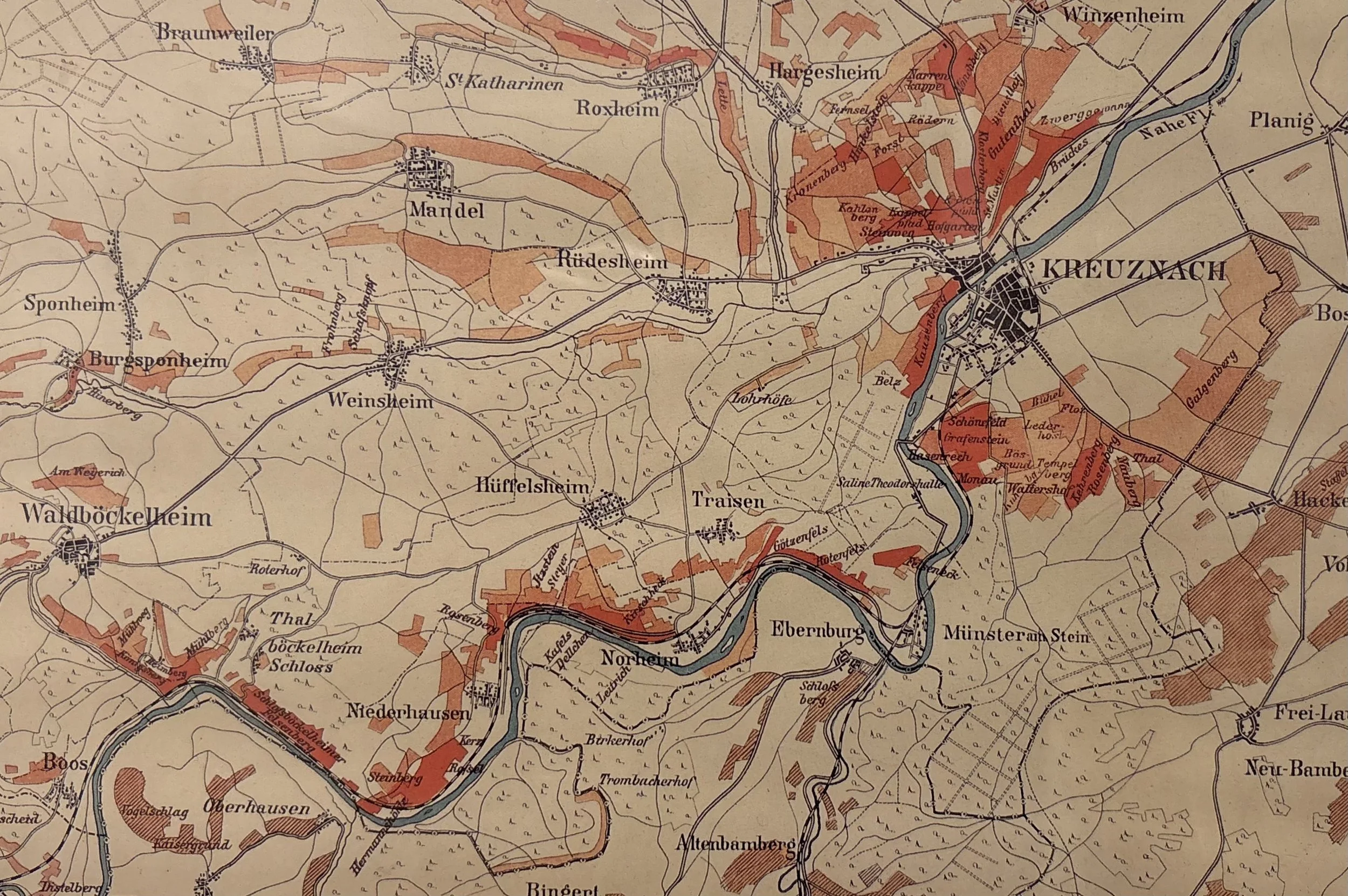

From Cabinet to Kabinett

German wine has a well-deserved reputation for its intimidating nomenclature, but in the case of the easily pronounceable term “Kabinett”, it’s the history of the word that’s complicated. For hundreds of years it was spelled “Cabinet” and used unofficially to denote a wine that was deemed to have special characteristics, key among them being exceptional ripeness. The word referenced the secret chambers or “cabinets” within vaster cellars wherein a producers’ most prized bottles would be stashed away. Still today, some of the growers that we work with who occupy ancient cellars have schatzkammers within them—rooms where special bottles from great vintages slumber under lock and key.

By the 19th century, the term “Cabinet” was increasingly found on German wine labels—particularly, but not exclusively, in the Rheingau region. Connoisseurs would infer a wine made from overripe grapes, almost certainly harvested from a famous vineyard, and in exceptional cases the word was even used in tandem with “Auslese” to further bolster that prestigious designation. Despite its lack of official regulation, it’s clear that producers and traders of German wine didn’t use the word “Cabinet” casually or lightly.

In 1971, the German government initiated a new wine law that changed the meaning, and spelling, of “Cabinet” forever. The prädikatswein system within the new wine law established a quality hierarchy based on the ripeness of grapes at the time of their harvest. Within this hierarchy are specific categories of ripeness, the most modest of which was inexplicably designated “Kabinett”. It must be noted that most of the commodity wines made from Riesling in this decade didn’t qualify for any of the categories, and especially in challenging vintages, the achievement of Kabinett-level ripeness was considered commendable. The growing seasons were cooler then, and most growers didn’t farm with the meticulousness that they do today. Yet for several decades and up until very recently, Kabinett was viewed by many within the wine world as a vinous compromise to the richer, riper Spätlese and Auslese wines—not to mention the rare dessert styles that would qualify for the Beerenauslese and Trockenbeerenauslese categories.¹

Kabinett Gets Thick ‘n’ Sweet

As the decades passed, growing seasons became warmer and a particular flaw of the prädikatswein system became increasingly glaring. Although each category stipulates a minimum level of ripeness, no maximums are imposed, and while achieving Kabinett levels of ripeness might have been a challenge in the 1970s, by the late 1990s and early 2000s these minimums were effortlessly exceeded in almost every vintage. The fact that the fashion among journalists and consumers during these times was for opulent, richly hedonic wines didn’t help either, and not nearly enough of them championed the qualities that make German Riesling unique in the wine world—namely, the potential for intensity and complexity of flavour (not to mention unbridled drinkability) without an excess of weight or texture.

Noticing that richer and sweeter Rieslings tended to receive higher scores with critics and therefore engendered better sales, many winegrowers actively helped Mother Nature push their wines further in this questionable direction. By the late 2000s, most Kabinett Rieslings were riper and sweeter than the average Auslese from the 1970s, and these terms—along with Spätlese—could only be said to be indicative of style in a relative sense within a particular producer’s portfolio. There were German wine lovers at the time who argued that paying Kabinett prices for what is actually Spätlese or Auslese ripeness makes for great value, and there were others (like me) who bemoaned the increasing absence of Germany’s most singular and distinctive category. Ripeness for its own sake isn’t a virtue, and sweetness without other qualifiers isn’t worth celebrating either. In the meantime, one of the world’s most useful and inimitable wine styles was becoming an endangered species.

Lightness As a Virtue

Only in the past decade or so, a couple of circumstances have catalysed an undeniably positive change for Kabinett. The 2014 growing season offered winegrowers the first chance since at least 2008 to harvest modestly-ripe grapes for delicate, low-alcohol, low-sweetness, high-acid wines without radically adjusting their protocols in the vineyard. This was perfectly timed with the overdue swinging of a German wine pendulum. In recognition that light, off-dry Rieslings with intense and profound flavours are irresistible and more or less unique to Germany, a small number of high-profile producers—Keller and Schätzel in the Rheinhessen are of particular note—began to promote and price their single-vineyard Kabinetts in a way that raised eyebrows while demanding the attention, and eventually respect, from the wine-buying public.

The fact of the matter is that in the 1970s, the exceedingly ripe category of Auslese was only possible when particular weather combined with careful, strategic harvesting on the part of the winegrower. In what might be called an “average” vintage today, it’s Kabinett that requires an intentional pursuit if one wishes for their version to be a genuine example of the category. A winegrower must actively mitigate ripeness in the vineyard and time their harvest carefully, which can be done in various creative ways—all of which require some combination of effort, talent and determination. And then, every once in a long while, there’s a vintage like 2024…

In a way that’s become increasingly rare, the struggle to ripen grapes in Germany was very real in 2024, and the Kabinett level of ripeness served as a sort of natural average limit for sugar accumulation. So there’s an abundance of Kabinett which doesn’t automatically mean it’s a great vintage for the style—there's no shortage of lacklustre Kabis out there. But talented winegrowers who value Kabinett as a singular and crucial expression of Riesling succeeded in bottling fundamental masterpieces that embody the theoretical combination of a marginal 1970s growing season with today’s unyielding and highly-sacrificial pursuit of quality. Such Rieslings are electric, thrilling, crystalline, gossamer, excruciatingly flavourful, and virtually weightless with nuances that channel rocks, vapours, blossoms and dreams. At the very top level they tattoo themselves into the tongue with their relentless saltiness and are distinct from their commendable 2021 counterparts by being even more compact, dazzlingly pixelated, and gloriously precarious in their levitating harmony.

A.J. Adam’s 2024 Kabinetts

Although they don't necessarily have a monopoly on this level of quality, nobody made better Kabinett in 2024 than Andreas Adam and his sister Barbara Gudelj. Their 6.8-hectare Mosel estate epitomised the bright side of the vintage, and in light of the history of Kabinett outlined above, I'll be so bold as to say that the four wines below are among the greatest “genuine” Kabinett wines that anybody has made in the past 53 years. They are animated, whisper-sweet, barely-alcoholic, tensile Rieslings of shattering, eloquent delicacy. More profoundly, they’re soul-stirring conduits to the natural world that starkly demonstrate the disparate personalities of the respective vineyards from whence they grew, each being a reason to rejoice in the miracle that is wine.

I recognise that offering all four options is a commercial nightmare, but having tasted their masterful splendour as a cohesive and mutually complementary lineup, I refuse to deny anybody else the opportunity to do so.

Finally, and to be completely shameless while also being completely honest, I would highly recommend going deep on these where quantities allow (we have better supply on some than others). Who knows when Mother Nature will provide the opportunity for this sort of Kabinett vintage again, and when she does, the wines (like everything else) will probably be a lot more expensive. These are bottle-per-head Rieslings that give great pleasure now, and will continue to do so for many, many Christmases to come.

2024 Häs’chen Kabinett $55 SOLD OUT

“Häs’chen” means “little hare” and this tiny ungrafted vineyard—a monopoly of A.J. Adam—would be as cute as its name if it wasn’t so perilously steep. In a feeble attempt to prevent clutter, we’ve never worked with this cuvée but in 2024 it was simply impossible to decline. The crystal clear aromas channel bergamot, slivers of peach and yellow apple, all transmitted along high voltage wires of volatile sunshine and some ineffable foreshadowing of the psychotic torque that follows on the palate. It’s a ripper! Glacial clover, chiselled ozone, intergalactic citrus… Experiencing so much concentration and flavour in a wine that’s also so light is clearly a contravention of physics, or maybe chemistry… Damn! The bottle’s already empty and thus ends the tasting note.

2024 Hofberg Kabinett $55 AVAILABLE

This is Adam’s home vineyard, the holdings of which make up the majority of the estate. This means that it’s the most readily available of the lineup, and also that it’s usually the most “complete” wine because there’s more land to draw from. In a typical vintage, Hofberg Kabinett comes from deep within this side-valley perpendicular to the Mosel River, but 2024 is decidedly not a typical vintage, and this year’s version is sourced from throughout the site—including revered parcels of ancient vines that are usually dedicated to more expensive cuvées. I love this wine unconditionally. To the extent that we can speak of fruit, we’re deep in the apple and cherry zone which is a hallmark of Hofberg, but it’s also salty as fuck, pixelating on the palate into red lightning for the synesthetes. What one is left with is a punishing, spiritual sense of harmony strung along an interminable finish and the evaporative conviction that if something like this can grow out of the ground, the world can’t be as bad as we thought.

2024 Ohligsberg Kabinett $59 AVAILABLE

Though it usually takes site and vintner longer to become acquainted in order to achieve this level of mastery, Adam’s sophomore vintage with this legendary and precipitous vineyard has resulted in a distinctly spellbinding Kabinett (and GG, coming in early 2026). Indeed, it gives the Hofberg a run for its money but has an entirely different, stone-strewn personality. It channels the purity of slate, assuming a stoic austerity and though the acidity is literally off the charts, the wine communicates an extraordinary sense of stillness and tranquility. What little fruit is here dwells resignedly under a carpet of pristine moss, and the intricacy of salty, sylvan charm annihilates the scant residual sugar and perpetuates itself through a prolonged, salivating crescendo. After tasting this sample, I had to wander outside for a minute to collect myself before going on… Don't miss this!

2024 Goldtröpfchen Kabinett $59 SOLD OUT

Like Falkenstein’s similarly supernal Euchariusberg Kabinett from this vintage, this one snuck through the system despite not quite reaching the minimum ripeness for Kabinett. It’s testament to how far the pendulum has swung that German wine lovers like me are delighting in this fact and the levity it guarantees instead of criticising its lack of grander ripeness. It’s brittle blossom juice, featherweight, saline, edgy and effectively “dry”, emanating its regal, neon bitterness through a gallantly sinuous framework. I’ve never before tasted a Goldie Kabinett like this, the most classic and antediluvian of Adam’s masterful 2024 Kabinett range.

Also available:

2024 A.J. Adam Riesling Feinherb “im Pfarrgarten” $36

2024 A.J. Adam Hofberg Spätlese $77 (limited - total production was 1000L)

2024 A.J. Adam Hofberg Auslese $86 (very limited - total production was 400L)

Halloween '25

October is for watching horror movies and a couple of nights ago it was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for the thousandth time. The cats were lackadaisically strewn about the couch to enjoy the carnage too, entering into an unspoken human and feline showdown as to who could be the most languorous. The cats always win.

Save Alberta’s Dying Wine Industry

The ad valorem wine tax is an unprecedented change in Alberta’s 30+ years of privatized liquor history. We have never had a system different to the standard flat rate. Therefore we are calling for this new ad valorem tax to be reviewed and revised a year after its effect. There are a plethora of small independent businesses in Alberta that will not be able to survive the 5 years before this change is reviewed. The continued erosion of businesses and wines in our province will lead to a sterile landscape where Albertans have little choice. This is detrimental to the livelihoods of Albertans both economically and culturally.

In Lieu of a Political Statement

It's hard not to write about politics these days, despite having effortlessly avoided doing so my entire life. While admitting that readers of these pages probably land all over the political spectrum, it would be hard for any of you to deny that politicians everywhere have been especially provocative as of late. But I'll resist the urge to weigh in and will instead share a story from my weekend.

Full Moons, Lunatic Art and Warm September Evenings

One evening this week I was completely spellbound by the beauty of a wine that came my way. It was a mature bottle from a producer whose lofty reputation I had long felt was unjustified, and the experience changed my mind by blowing it. But I've been writing too much about wine lately and would rather share another example of the disarmingly auspicious impact of unexpected profundity.